SUBI in the New York Times on November 17, 2013, on page MM18

SUBI = swiss universal basic income or swiss unconditional basic income

Switzerland, a new way for a real ecomic democracy, the swiss unconditional basic income

The swiss secrets:

One current study which polled people in 221 cities around the globe has

placed three Swiss cities in the list of the top ten places to live in

worldwide: Zurich, Geneva, and Bern. We find out why Switzerland is so

attractive.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtG1O_JUOdM

Switzerland is set to vote on whether to introduce a basic income for

all adults after a grassroots group submitted more than the 126,000

signatures needed to call a referendum. Campaigners are calling for an

unconditional income of 2,500 Swiss francs (€2,000/$2,800) per month and

illustrated what they see as Switzerland’s cash piles by dumping

truckload 8 million five-rappen coins outside the parliament building in

Berne. This video by the group behind the campaign, Grundeinkommen,

shows activists with the 8 million coins. Credit: Youtube/Grundeinkommen

“We Swiss are all Kings, and the first duty of a King is to control the money creation, actually robbed by the bankers.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqKkERp-ias

126’408 signatures, vote YES to UBI (unconditional basic income) alias SUD (Swiss unconditional dividend) or

SUBI = swiss universal basic income or swiss unconditional basic income

The initiative for a basic income has been declared valid by the Federal Chancellery

On November 8th, the Federal Chancellery announced that the federal

popular initiative for an unconditional basic income has formally ended.

After verification of signatures, 126’408 valid signatures were filed on October 4. The Federal Chancellery is clear: a referendum will be held.

And now, what will happen? The Federal Council will look at the basic

income and prepare a report on the subject. He’s a year for it. Then

open the debate in Parliament. As for the popular vote, it is provided

by two or three years.

The question is: every person in this country should it receive an unconditional financial base sufficient for him to live?

Source: http://bien.ch/fr/story/actualites/chancellerie-federale-linitiative-formellement-abouti

Switzerland is forward progress and adapt to new conditions, robots, machinery, computers and automation.

The new money distributed will not come from taxes or wages, but will distribute the abundance made possible by automation and the

creation of money which is now actually “given” by the bankers billion

or more centuries …

These quantitative easing should be given

to the people, not for war and premiums to rare happy fews … The

new Swiss company for true economic democracy finally distribute the

income of technical progress, natural resources, automation more

efficient, thanks to robots, computers and machines.

A new company, the animals are free, it’s our turn, free human beings, we free ourselves from the chains of bondage.

dividends for all Swiss people, people of all States of the Swiss

Confederation, here is a real economic democracy, thanks to robots,

computers and machines.

http://desiebenthal.blogspot.ch/2013/10/the-rubin-report-switzerland-basic.html

We Swiss are all kings, and the first duty of a king is to control the money supply.

They are billions and quadrillions for stupid wars, we prefer to invest this money in peace.

Dividend or royalty?

It’s the true and real democratic Economy

Switzerland’s Proposal to Pay People for Being Alive

By

ANNIE LOWREY

Published: November 12, 2013 Comment

building in Bern, one for every Swiss citizen. It was a publicity stunt

for advocates of an audacious social policy that just might become

reality in the tiny, rich country. Along with the coins, activists

delivered 125,000 signatures — enough to trigger a Swiss public

referendum, this time on providing a monthly income to every citizen, no

strings attached. Every month, every Swiss person would receive a check

from the government, no matter how rich or poor, how hardworking or

lazy, how old or young. Poverty would disappear. Economists, needless to

say, are sharply divided on what would reappear in its place — and

whether such a basic-income scheme might have some appeal for other,

less socialist countries too.

Enno Schmidt, a leader in the basic-income movement. He knows it sounds a

bit crazy. He thought the same when someone first described the policy

to him, too. “I tell people not to think about it for others, but think

about it for themselves,” Schmidt told me. “What would you do if you had

that income? What if you were taking care of a child or an elderly

person?” Schmidt said that the basic income would provide some dignity

and security to the poor, especially Europe’s underemployed and

unemployed. It would also, he said, help unleash creativity and

entrepreneurialism: Switzerland’s workers would feel empowered to work

the way they wanted to, rather than the way they had to just to get by.

He even went so far as to compare it to a civil rights movement, like

women’s suffrage or ending slavery.

Like many German words, it has no English equivalent, but it means

something like “coherent and harmonious,” with a dash of “beauty” thrown

in. It is an idea whose time has come, he was saying. And basic-income

schemes are having something of a moment, even if they are hardly new.

(Thomas Paine was an advocate.) But their renewed popularity says

something troubling about the state of rich-world economies.

off about the benefits of a basic income, just as you might hear someone

talking up Robin Hood taxes in New York or single-payer health care in

Washington. And it’s not only in vogue in wealthy Switzerland.

Beleaguered and debt-wracked Cyprus is weighing the implementation of

basic incomes, too. They even are whispered about in the United States,

where certain wonks on the libertarian right and liberal left have come

to a strange convergence around the idea — some prefer an unconditional

“basic” income that would go out to everyone, no strings attached;

others a means-tested “minimum” income to supplement the earnings of the

poor up to a given level.

that Congress decided to provide a basic income through the tax code or

by expanding the Social Security program. Such a system might work

better and be fairer than the current patchwork of programs, including

welfare, food stamps and housing vouchers. A single father with two jobs

and two children would no longer have to worry about the hassle of

visiting a bunch of offices to receive benefits. And giving him a single

lump sum might help him use his federal dollars better. Housing

vouchers have to be spent on housing, food stamps on food. Those dollars

would be more valuable — both to the recipient and the economy at large

— if they were fungible.

reduce the size of our federal bureaucracy. It could take the place of

welfare, food stamps, housing vouchers and hundreds of other programs,

all at once: Hello, basic income; goodbye, H.U.D. Charles Murray of the

conservative American Enterprise Institute has proposed a minimum income

for just that reason — feed the poor, and starve the beast. “Give the

money to the people,” Murray wrote in his book “In Our Hands: A Plan to

Replace the Welfare State.” He suggested guaranteeing $10,000 a year to

anyone meeting the following conditions: be American, be over 21, stay

out of jail and — as he once quipped — “have a pulse.”

as an anti-poverty and pro-mobility tool. There happens to be some hard

evidence to bolster the policy’s case. In the mid-1970s, the tiny

Canadian town of Dauphin ( the “garden capital of Manitoba” ) acted as

guinea pig for a grand experiment in social policy called “Mincome.” For

a short period of time, all the residents of the town received a

guaranteed minimum income. About 1,000 poor families got monthly checks

to supplement their earnings.

done some of the best research on the results. Some of her findings were

obvious: Poverty disappeared. But others were more surprising:

High-school completion rates went up; hospitalization rates went down.

“If you have a social program like this, community values themselves

start to change,” Forget said.

is one. Creating a massive disincentive to work is another. But some

experts said the effect might be smaller than you would think. A basic

income might be enough to live on, but not enough to live very well on.

Such a program would be designed to end poverty without creating a

nation of layabouts. The Mincome experiment offers some backup for that

argument, too.“For a lot of economists, the issue was that you would

disincentivize work,” said Wayne Simpson, a Canadian economist who has

studied Mincome. “The evidence showed that it was not nearly as bad as

some of the literature had suggested.”

have resurfaced of late. Wages are stagnant, unemployment is high and

tens of millions of families are struggling in Europe and here at home.

Despite record corporate earnings and skyrocketing fortunes for the

college-educated and already well-off, the job market is simply not

rewarding many fully employed workers with a decent way of life.

Millions of households have had no real increase in earnings since the

late 1980s. Consider the current debate over fast-food workers’ wages.

10-year McDonald’s veteran, Nancy Salgado, when she contacted the

company’s “McResource” help line. The operator told Salgado that she

could qualify for food stamps and home heating assistance, while also

suggesting some area food banks — impressively, she knew to recommend

these services without even asking about Salgado’s wage ($8.25 an hour),

though she was aware Salgado worked full time. The company earned $5.5

billion in net profits last year, and appears to take for granted that

many of its employees will be on the dole.

already exists in a way — McDonald’s knows it. If our economy is no

longer able to improve the lives of the working poor and low-income

families, why not tweak our policies to do what we’re already doing, but

better — more harmoniously? It’s hardly uplifting news, but minimum

incomes just might be stimmig for the United States too.

A version of this article appears in print on November 17, 2013, on page MM18 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: Take One Income, Please.

It’s the Economy

Readers’ Comments

Share your thoughts.

European petition: http://sign.basicincome2013.eu

US webpage: http://www.usbig.net/index.php

Australia: http://www.basicincome.qut.edu.au/

South Korea: http://cafe.daum.net/basicincome

Swiss basic income or royalty, arguments

http://www.streamica.com/#v/m0Mne9wDGV4

problem is not in our case inflation because our robots are producing

nearly everything at very low prices. The problem is the distribution of

this massive new production by new money or vouchers.

Our decentralised states and communes have most of the power, not the

central gov., i.e. most of the wealth is private or communal and

cantonal, i.e. the most rich per capita of the real world are the

swiss.

-

Modern Switzerland has

been constituted out of 25 sovereign (6 half cantons) cantons with the

first Federal Constitution of 1848.

say the Swiss are the richest people in the world, with net financial

assets of nearly $148,000 per capita. That is a third more than the

average for the next two wealthiest nations—Japan and the United States. And when it comes to distribution of income, Switzerland is one of the most equal societies.

Europe’s second-wealthiest country is

Switzerland. The Swiss economy has performed remarkably well despite its

proximity to recession-battered European nations. Switzerland’s GDP

grew 3% in 2010 and an estimated 0.9% in 2012. Those aren’t eye-popping

numbers, but compared to Europe’s far-reaching contraction, it’s a

relieving dose of stability. Swiss citizens have gained from the

country’s notoriety as a tax haven, and the country’s forward-looking

moves — such as its preliminary agreement to a free-trade deal with

China — should only benefit its economy in coming years. The IMF

expects Switzerland’s GDP per capita to rise officially to more than

$54,000 by 2018.

is a smart use of technology and the opposite of the approach of

Anglo-Saxon industrial dairies, who forced their cheeses into shapes

that could fit more readily into an existing logistical system.

Vacuum-packed blocks are easy to mature—they can be turned with a simple

forklift truck—but already you have compromised the character of the

cheese. In that case the machines dictate to the cheesemaker. In

contrast, whenever he installs a new machine, Alain Sugnaux makes the

same point to his customer: “The skill for the man is to control what

the robot is doing.” A robot never rushes and never becomes distracted.

It glides along the shelves of the cheese store with serene mechanical

grace, exactly repeating the same gentle handling for each cheese. With

cheese good robots enable good artisans.

125’000 signatures for the swiss unconditional basic income

new money is not coming from taxes or salaries but from the money

creation actually given to the bankers by billions or even

quadrillions…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqKkERp-ias

Swiss quantitative easing ( S.Q.E.1) not only for bankers but for all swiss peoples.

Automation will benefit to all. Let’s share the massive productivity. 125’000 signatures for the swiss unconditional basic

income (SUBI), a dividend for all swiss peoples, inhabitants of all the

States of the Swiss Confederation. 8 millions coins, one for each of

us. For us the living.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/For_Us,_The_Living:_A_Comedy_of_Customs

Swiss Open Society to a real economical democracy,

let’s distribute the incomes from more and more automation, thanks to

robots, computers and machines.

A new society, animals are free, it’s our turn, let’s free human beings from the chains of serfdom.

We, swiss, are all Kings, and the first duty of a King is to control

the money creation, actually robbed by the bankers…

http://desiebenthal.blogspot.ch/2013/02/infinite-interest-rate.html

http://vimeo.com/76259115

4th October is history, the feast of St Francis of Assisi, we have the

chance for a basic income event for Europe and the world.

The sun was there… http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canticle_of_the_Sun

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_of_Assisi

The 4th of October is a major event for the international Basic

Income community. The + 125’000 signatures collected in Switzerland

since

April 2012 for the popular initiative for an unconditional basic income

has been handed over to the Swiss parliament. It means a lot : within 4

years every Swiss citizen will know the idea of unconditional basic

income and have to vote on whether they

want or not a basic income. It will be the first time in history that

the people of a country can make this choice. Switzerland is showing

every country the way towards the introduction of a basic income.

All citizens, journalists and everyone were warmheartedly welcome to

join this major event ! Thank you, all journalists from abroad who came

to participate and broadcast this importnat event.

This Friday, 4th October, Bundesplatz 3, in Bern.

Signatures have been handed over to the Federal Chancellery at 11 a.m.

Then we had a prepared lunch together and finally we will have a party at 8pm

in the «Turnhalle», next to Bern station.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqKkERp-ias

Swiss quantitative easing ( S.Q.E.1) not only for bankers but for all swiss people.

The Swiss initiative in details :

The popular initiative for an unconditional basic income (UBI), which

in the view of its supporters should be thought of as a civil right

rather than social wefare, was launched in 2012. It aims to have a new

clause incorporated into the Swiss constitution that the Confederation

“shall ensure the introduction of an unconditional basic income. The

basic income shall enable the whole population to live in human dignity

and participate in public life. The law shall particularly regulate the

way in which the basic income is to be financed and the level at which

it is set.”

The success of the Swiss initiative could have model character for the whole of Europe and even the world.

http://www.rts.ch/info/suisse/5265891-l-initiative-pour-un-revenu-de-base-de-2500-francs-deposee-a-berne.html

Meaning of the coat of arms: Chapel of Gstaad, St Niklaus.

Let the dragon that is in each of us within 7 locks.

Swiss safe solutions:

-

Thousands of honest and hard working citizens are saddled with debts and living at or beneath the poverty line. At the same time the government is shaving funding from citizen priorities such as health care, education, unemployment benefits, job creation initiatives, new start-up enterprise assistance incubators, environmental protection, infrastructure maintenance and local public transportation. As well, at a time when Switzerland more frequently finds herself isolated on the inter-continental (European Union) and international stage, the government continues to slash public support to our diplomatic and embassy bureaus and our Post office modernization. Pension funds continue to be under funded and in some cases are being stripped of their assets. In this environment I it any wonder that our cherished bonds of cohesion and solidarity are fraying?

-

The above “solutions” are part of a long series of sneaky, underhanded forms of money grabbing through more efficient and effective parking meters, automated speed and other traffic code revenue generation automation in conjunction with a host of new user pays licences and registration requirements across all pastimes and activities. As well the regressive sales tax, jokingly called “Value added” has been increased while the categories exempted have been reduced, penalizing all citizens but particularly the poorest as well as the once vibrant small and medium size enterprises (MSE) faced with reduced customer purchase revenues and increased regulatory costs. This reality has reduced both current employed numbers and positive expectations for the future, particularly among the young and recent graduates.

-

Meanwhile the economic reality of production of goods and services, thanks to the many discoveries and inventions such as computers and robots is a constantly more efficient economic system producing a greater abundance of these goods and services but also dramatically reducing the human input required. This off course results in a not infrequent over production of goods, while at the same time reducing the number of jobs and human hours of work required. A growing proportion of the population is thus deprived of their “pay-cheque”, their only means to acquire the goods created within and by their own communities. This unfortunately tempts and forces some into activities for money that are shameful and or illegal.

-

A new crisis at Union de Banques Suisses or any too big to fail banks could necessitate billions in Federal Council emergency funds underwriting the gambling losses of such bank. This means that generations of current and future taxpayers will be paying for the bank’s mistakes, and also get to pay interest on this privilege! So let’s stop right here and add up what we’ve looked at so far: production results and capacity are abundant having wisely built on our long traditions of inventiveness and innovation, particularly in the processes and equipment used in production; this progress while good in itself, had dramatically reduced the demand for human input , therefore employee or wage workers. This means for many either a reduced pay cheque due to reduced hours or no job now nor in the future. No pay cheque means no means to acquire the good which are being more abundantly produced. Meanwhile, despite having less and less “pay cheque” money, we are being subjected to higher and higher punitive surveillance and regulatory requirements and fees. And now, let’ get this right, the small minority that has excessive amount of pay cheque money, dividends from un-taxed trust funds, huge returns from capital invested who knows where and in what, the ones who guessed wrong or gambled unconsciously requiring these massive tax subsidized bailouts further reducing all our disposable or purchasing totals, these same people profit again by pushing down the price they pay for products and services since there are fewer and fewer buyers? Does this all add up for you? No, well it doesn’t seem to be adding up any better for the hundreds of thousands, millions of our fellow humans taking to the streets in Ireland, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, anywhere in Europe. If we widen our scope we quickly see it isn’t adding up anywhere else in the world either.

-

Two Archetypes of this dysfunctional system are the privately owned Federal Reserve Bank of America and its privately chartered collection agency the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) These systems were both designed by international bankers and vested individuals who through verbal duplicity and ambiguity to tricked the unsuspecting American citizens by their Congressional representatives to permit the “FED” exactly a hundred years ago in December 1913. These two archetype are representative of the “Too big to Fail” syndrome so familiar today—their toxic assets create by the perverse mechanism of private money creation from nothing are hailed as saviours of the sovereignty. For more than three centuries a small elite group has been creating billions and billions of dollar, francs, yen, based debts for all of us, plus interest off course, using our properties, homes, businesses and public treasures and common infrastructures. They get the cash, we get the debt! Our debt, besides being morally depraved, is also mathematically impossible to re-pay. Every culture recognizes, as do all the moral codes, that contracts which by their terms of required performance are impossible to perform are void from the outset!!All sovereign jurisdictions and many corporations, families and individuals are beyond the point of no return due to this abdication of responsibility in the past at the sovereign or nation state level. The few nations that have recently tried to resist , such as Libya, have been bombed back into the stone ages of anarchy, destitution and hopelessness. This lopsided global system of systemic boom (new debts “borrow money to make money”) to bust ( dramatic contraction of the money supply) is not an “invisible hand” any longer. The liars’ talk of “fiscal responsibility” was conceived in inequity and implemented knowingly or unknowingly with the majority of head of state, elected representatives and international governing bodies such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) . Will we continue with our children and their children to be slaves of this self appointed banking “elite” who have created the life blood of our economic exchange system (money) putting nothing in and yet essentially controlling everything?

-

THERE ARE SOLUTIONS CURRENTLY BEING PROMOTED HERE IN SWITZERLAND

-

François de Siebenthal: Kennedy’s robolution against banksters’ss …

30 sept. 2011 – Kennedy’s robolution against

banksters’ss debts at interests. The 5 dollar with the red seal

(without interest) and not the green seal ( please, … -

François de Siebenthal: Wall-Street, occupation, Global Robolution

23 sept. 2011 – Wall-Street,

occupation, Global Robolution. Protesters gather in Wall-Street, the

New York’s financial hub for demonstration against what …

-

switzerland: subsidiarity, power-sharing, and … – Andreas Ladner

principles

of constitutional recognition are subsidiarity and municipal autonomy.

Both emphasize the importance of subnational governments in Switzerland. -

Switzerland: Subsidiarity, Power‐Sharing, and Direct Democracy …

This

article discusses the Swiss political system which is marked by

symmetric federalism. In Switzerland, subnational democracy is accorded

with the same …

More Echoes from all over the world:

http://www.indiatimes.com/news/europe/when-8000000-five-cent-coins-were-dumped-pics-105006.html

Even Israel is on the way: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmjs3SGQP3U

http://gb.cri.cn/42071/2013/10/05/5892s4273991.htm

|

瑞士另类示威 8百万枚硬币倾倒国会大楼前(高清组图) – 新闻 – 国际在线

瑞士另类示威 8百万枚硬币倾倒国会大楼前(高清组图)

|

Blick

(um 16.00 gab es auf dem Onlineportal bereits 500’000 Klicks)

20 Minuten

SRF Tagesschau

NZZ

Tagesanzeiger, Bund, Berner Zeitung und weitere Tageszeitungen der Schweiz

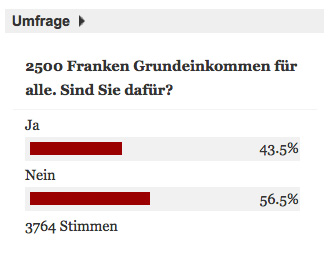

(Onlineabstimmung: Stand 4.10 23.55: 43% Ja – 57% Nein)

Süddeutsche

Dailymail

Yahoo.com

Russia Today

Sat1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqKkERp-ias

http://www.latele.ch/play?i=38811

http://www.lematin.ch/suisse/peuple-dira-s-veut-dun-revenu-2500-francs/story/20672679

http://www.ouest-france.fr/ofdernmin_-Suisse.-Vers-un-revenu-minimal-equivalent-a-2-000-_6346-2235621-fils-tous_filDMA.Htm

http://inserbia.info/news/2013/10/swiss-threw-usd-440000-on-the-street-as-a-protest/

http://fr.reuters.com/article/frEuroRpt/idFRL6N0HU2UJ20131004

http://www.parlamentnilisty.cz/profily/Martin-Shanil-21337/clanek/Prisne-tajne-17913

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/10/04/us-swiss-pay-idUSBRE9930O620131004

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2443812/Streets-Basel-paved-gold-15-TONS-cent-coins-dumped-citys-streets-protesters-demand-increased-minimum-wage.html

http://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/news/international/Swiss_to_vote_on_2,500_franc_basic_income_for_every_adult.html?cid=37048792

http://www.carbonated.tv/news/switzerland-to-have-vote-on-income-for-everyone

Bern, 4. Oktober 2013 – ein historischer Tag!

Eine freudige und erwartungsfrohe Stimmung prägte den Tag auf dem

Bundesplatz in Bern. Über 1000 Menschen erlebten live die Einreichung

der Volksinitiative zum bedingungslosen Grundeinkommen. Die Performance “Kopf oder Zahl” der Generation Grundeinkommen lösste ein Flut von Medienbeiträgen aus. Selbst ein Russisches und ein Chinesisches Fernsehteam war vor Ort.

Hier eine erste Auswahl:

Blick (um 16.00 gab es auf dem Onlineportal bereits 500’000 Klicks)

20 Minuten

SRF Tagesschau

NZZ

Bote der Urschweiz

Cash

Tagesanzeiger, Bund, Berner Zeitung und weitere Tageszeitungen der Schweiz

(Onlineabstimmung: Stand 7.10 23.55: 43% Ja – 57% Nein)

International:

FAZ

Süddeutsche

Dailymail

Yahoo.com

msn (weltweit)

RT – RUSSIA TODAY (Ausschüttung)

RT – RUSSIA TODAY (Einreichung und Interviews)

Sat1

cri.online (China)

voakorea (Korea)

Zeit.de (Bilde des Tages)

euro.news

Le Matin

RTS

Tribune de Geneve

The National (das führende englischsprachige Magazin im Nahen Osten! Da ist das Reuters Bild das Beste der letzten 24 Stunden!)

Post (Südafrika)

Die Welt (Die besten Bilder des Tages)

Die Rote Fahne (Europäisch sozialistisches Magazin)

Mina (Mazedonien)

News.Mail (Russisch)

arabianbusiness.com

circa.news

GUARDIEN EXPRESS

inserbia (Serbien)

ZVONO (Kroatien)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixznTmkETng

Read More: switzerland, basic income, generation basic income, democracy, referendum, government, swiss government, income inequality

Commentaires récents